For most raw-material producers, less supply can mean higher prices and more profit. Not so much for gold.

With bullion near a five-year low and investors unloading metal they hoarded for about a decade, some mining companies are losing money and output is poised to drop for the first time since 2008. If history is any guide, the cutbacks will have little impact on the market.

Gold is viewed mostly as a financial asset, from bars and coins to jewelry passed down to heirs, and every ounce ever dug up from the earth is still in existence, with recycled metal accounting for more than a quarter of annual supply. When mines last trimmed operations, bullion still slid as much as 29 percent into a bear market. Even surpluses in 2010 and 2011 didn’t prevent prices from reaching records.

“The question mark is whether or not closing production is going to make a blinding bit of difference to the gold price,” said Paul Gait, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. in London.

Mine Production

Global mine output surged 24 percent in a decade to a record 3,114 metric tons in 2014, as companies dug more to exploit a 12-year bull market in prices, according to data from industry researcher GFMS, a unit of Thomson Reuters Corp. Bloomberg competes with Thomson Reuters in selling financial and legal information and trading systems.

About 65 percent of bullion that’s mined or recycled is used in jewelry or industrial items, with the rest sold to investors.

Gold has tumbled 40 percent from a record $1,921.17 an ounce in September 2011 as buyers lost faith in the metal as a store of value. Prospects for higher U.S. rates and a stronger dollar pushed the metal to $1,077.40 on July 24, the lowest since February 2010.

Bullion has rebounded about 5 percent to $1,136.37 since then as currency devaluations from China to Kazakhstan and a global selloff in equities boosted demand for a haven. Prices slid 1.6 percent as of 4:01 p.m. in London on Tuesday.

CEO Outlook

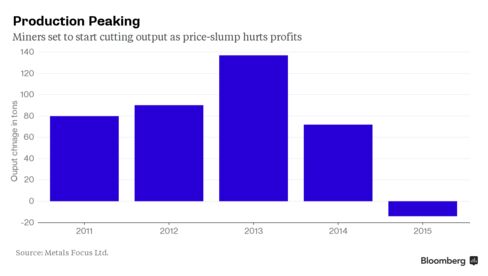

Even with the rally, prices aren’t high enough for some producers. About 10 percent of the world’s mines are losing money, according to London-based researcher Metals Focus Ltd. Output will start declining as soon as next year, said the chief executive officers at Randgold Resources Ltd. and Polymetal International Plc. Gold Fields Ltd.’s CEO expects a “big dip” from about 2018, while HSBC Holdings Plc predicted the drop will be 25 tons this year.

With prices at about $1,100, production probably will plunge 18 percent by the end of the decade, Metals Focus estimates. That’s because the industry, on average, needs about $1,200 to break even when all costs are considered, according to James Sutton, a portfolio manager at JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s $2 billion Natural Resources Fund.

Barrick Gold Corp., the world’s largest producer, will restrict output in the next few years, Moody’s Investors Service said Aug. 12, after cutting the company’s credit rating to one level above junk status. Profit margins for the 15 largest producers have dropped as much as 45 percent since 2011, while their debt has doubled to about $34.7 billion, according to an analysis by Bloomberg Intelligence.

Supporting Price

Cutting output by 5 percent would help balance the market and support prices, according to Mark Bristow, CEO of Jersey, Channel Islands-based Randgold. Gold will rebound 19 percent by 2017, partly as supply tightens, HSBC predicts.

“Exploration has been slashed, projects have been put on the back burner,” said Nick Holland, CEO of Johannesburg-based Gold Fields. “The gold industry supply side is going to drop.”

The implied gold surplus, which measures mine output and recycling against demand from jewelers, manufacturers and investors, will drop to 999 tons next year, the lowest since 2012, after reaching 1,476 tons in 2013, according to Barclays Plc.

Production cuts may take a while to affect prices because demand can be satisfied by recycling jewelry and using metal held in vaults, according to Georgette Boele, an analyst at ABN Amro Bank NV in Amsterdam. She forecasts gold at $800 by December 2016.

AngloGold Ashanti Ltd., based in Johannesburg, is one miner that’s had to cut some higher-cost production.

“Supply restrictions will come in,” said Srinivasan Venkatakrishnan, AngloGold’s CEO. “Mine supply, in the near term, has very little impact on the gold price.”

TSX up more than Dow at the moment. Does that say anything? Probably not, since oil is up.